I suppose long before the transaction and well before hindsight had a chance to kick in, I knew this wasn’t the best idea I’d ever had. But it fell into my lap, like a forgotten Christmas present, and being at my wits’ end and short of time, I really didn’t feel as if I had much choice.

They descended, like every year, on Christmas Eve. Although given the location of the old manse – high above Whitehills on the Moray coast – it was almost more appropriate to say they ascended if that didn’t give a greater religious lustre to the holidays than the Scott family would have appreciated.

The sisters, their various children, significant others and a few family friends – the waifs and strays of Banffshire with nowhere else to be – would gradually fill the old house until it seemed to resist the addition of any more bodies. Marianne had warned me it never seemed to get any warmer but had insisted I was welcome to join them all. I guess she felt sorry for the awkward looking lad at the end of the bar, the second night she’d spoken to me in The Market Arms.

Either way, I wasn’t too concerned. I welcomed the opportunity to get off the base for a day or two. To clear my head, sleep in a comfortable bed and see whether Marianne had more than a charitable interest in the boy at the end of the bar.

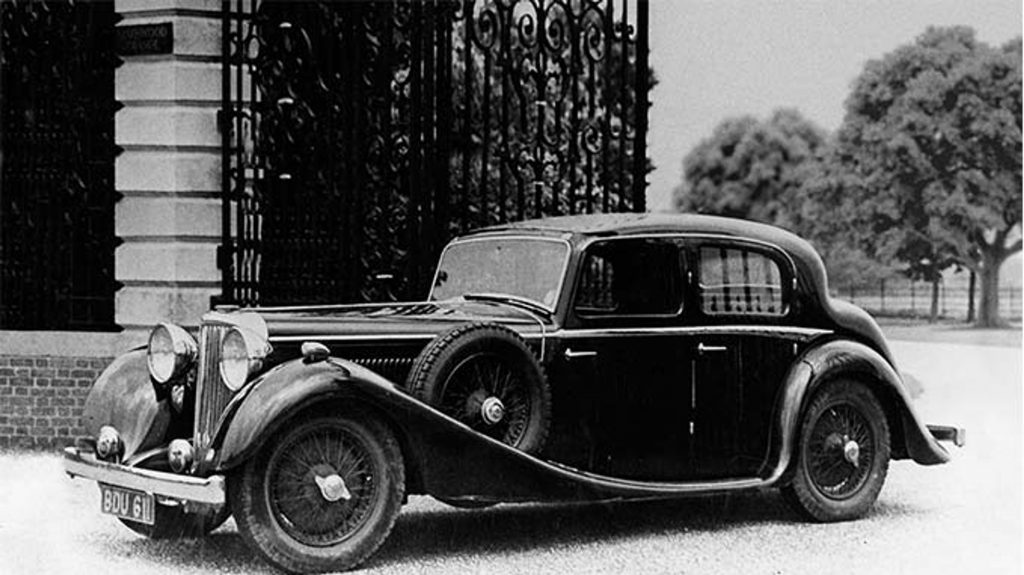

The early indications were good on the latter front. She was waving manically from the window of her father’s ageing Jaguar when they met me at the gates of the airbase on Christmas Eve, despite the gruff presence of her father Aiden.

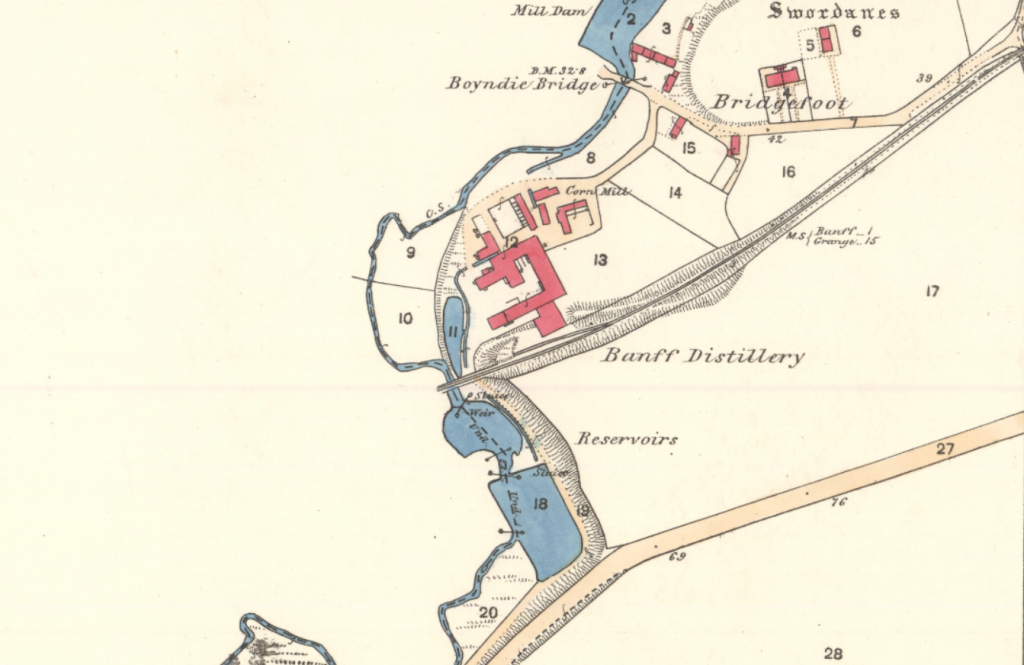

Everyone knew Aiden Scott. The local farm boy done good, he had returned to his hometown a few years ago, after making his fortune in Aberdeen. He’d snapped up the local distillery during one of the many slumps in the whisky industry, patched the place up and was enjoying a leisurely retirement tinkering away with the stills and stocks of one of the region’s lesser-known and little sought after distillers.

As a transient visitor, and not from the area, I knew little else, other than the airbase gossip about his four daughters. Two were now married and referred to only in glowing terms by the airmen who had known them about town before they were taken off the market, and the younger two broke no fewer than a squadron’s-worth of hearts on a regular basis, even if their visits home were now mostly limited to high days and holidays from their studies.

In any event, it’s fair to say that Marianne’s smile was sufficient to take my mind from my troubles as Aiden coaxed the car out of the lay-by and down the road towards Whitehills, and I slipped into polite small talk without too much further thought. Given the limits of my knowledge of Aiden Scott, I asked about his business. I’d heard about the warehouse fire, but he seemed relaxed, just a little annoyed about the angels taking more than their fair share, and the complaints from a neighbouring farmer that the spill of whisky through his fields had left him with a herd of drunk cows.

“You should invoice him for that” I suggested, “maybe the butcher will find his customers get the taste for whisky-soaked beef on their Christmas tables this year”. That seemed to ingratiate me with the old man, and he launched into a detailed commentary on lyne arms, and the strength of the unions forcing him to shut down production for two days over Christmas.

I suppose that was what first put the idea into my head.

As Marianne had warned me, the old house already felt full by the time we arrived, and the front door almost seemed to resist as she nudged it open and the draught from the large, wood-panelled hallway met us as we stepped in from the relative warmth of the December evening.

The grandchildren had already made themselves at home, a desultory streamer was wrapped from the newel post to the portrait of great grandfather Patrick, giving the old man a jollier look than he was accustomed to wearing.

“Oh thank goodness you’re here” – Allie Scott, the lady of the house, burst from the kitchen door and a blast of warm air followed her into the hall brushing past her middle daughter’s face before vanishing like a snuffed candle. “the new pavlova tray is too big for the Aga; I don’t know what I’m going to do. Oh, and this must be your new friend!”

Allie had a habit of referring to all of her daughters’ many suitors as ‘friends’. It may have been ten years since Ida, the eldest, had married, but the acceptance hadn’t trickled down to Marianne’s level. Her boyfriends, even that fiancé from two years ago, had never progressed beyond the friend tag.

Marianne confirmed that I was indeed her friend and we made our introductions, it was telling that she had ignored the unloading of the pavlova crisis, with the practised air of one who had learnt her mother’s trick of selective hearing.

“Still we’re all here now, although you can never tell what the Christmas morning breeze might blow in.”

I was ushered through to the kitchen. The only warm room in the draughty old house. It seemed like a hundred bodies were gathered around the dining table, the sink, the fridge and sundry other work surfaces. Somehow everyone found space in the room, and a tide of bodies moved as if with some practised form of balletic art, avoiding each other, and the furniture, while managing to achieve the many tasks that still seemed to require completion. Every flat surface was covered with dishes in preparation for the next day’s feast. I poked at the foil of a few and it appeared that most of them contained desserts.

Eventually, I saw my opportunity for a seat and sat down at one end of the kitchen table, adjacent to the youngest sister, Henriette who proceeded to grill me about life on base. Eventually, her attention started to wane.

“What’s that in your pocket?”

“Which?”

“There, the lump over your chest. Is it a bible? A framed photo of Marie?!”

“It’s my pocketbook,” I replied. I almost took it from my inside pocket but thought better of it.

“What’s in that? The phone number of every eligible young lady in Banffshire?”

“As if… No, it’s just notes.”

“What like ‘Oh, ‘dear diary, Marie is sooo dreamy…’’”

“No. It’s business. Creditors, debtors, that sort of thing”

“Ok, Mr Micawber, got to account for those pennies. Don’t want you succumbing to eternal misery. Would be no good for your looks.”

Once it became clear that I wasn’t keeping the diary of a pre-teen girl, Henri quickly lost interest in me and stood up to leave the room. She looked pleased with herself and was laughing as she brushed dismissively past her older sister and headed up the stairs.

The cold of the bedroom focussed my mind somewhat. I had just over twelve hours to settle my debts. There was no way I could get my hands on £3,000 in time, so I needed another option. It sounds clichéd, but I was actually pacing the room. I hadn’t realised people actually did that. From the half-shuttered window, I could see the moonlit lawn sloping gently towards the cliffs away to the left, with the woods providing a natural screen between the manse and the distillery.

I made up my mind and slipped out of the room and silently down the stairs. Aiden’s car keys were on the hall table, and the car parked far enough from the back of the house that I could start the engine and roll down the driveway without disturbing anyone. A few minutes later and I was outside the locked front gate to the Banff Distillery.

It wasn’t hard to spot the fire-damaged warehouse. The moonlight was sufficient to pick out the charred walls, and part of the roof had started to slip. Inside, the smell of vanilla, dried fruit and malt hung heavy. With a deep breath, I could almost taste it. I scanned the rows of casks. I didn’t know much about whisky, but I vaguely understood the older stuff tended to go for more money, and as most of the casks had a year scratched on the end, I selected one at the end of the row that was somewhere close to ten years old and rolled it back to the hole in the wall I’d entered by.

From here, the options were fence, railway line or field of cows. But to the right, the field sloped quickly away to the reservoirs that powered the mill. At water level the undergrowth was dense and the embankment high enough to keep it from view. The ground was muddy and uneven, but with an ungainly toe-poking action I managed to direct the barrel towards the riverbank.

Christmas morning was a continuation of the night before – a riot of activity. The children left parts of toys and packaging throughout the ground floor of the house, resolutely ignoring any request to tidy up after themselves. By mid-morning, most of the household was readying themselves for church. Allie had decided she needed to stay. The turkey couldn’t be left unattended, and the dessert trays were taking over the house. I tried to make my excuses citing my atheistic upbringing and slunk away to the sitting room. I hoped to wait for the family to leave for the short walk to the church before I could again borrow the car for my midday assignation.

The chatter dampened and the front door clicked shut. It seemed they’d all finally left, but instead, Marianne slipped into the room and sat down beside me on the sofa.

“What’s going on, mister?” she asked.

“Not a lot. I need to go into town. I have something I need to deal with.”

“On Christmas morning?”

“Yes.”

“Unless you’re Santa – and the evidence doesn’t look good – that doesn’t sound like a good something to be dealing with”

“It’s not particularly, but I’ve got it under control. I just need to borrow your dad’s car.”

“That shouldn’t be a problem, he leaves the keys by the door. I fancy a spin. I’ll come with you.”

“Marie, I don’t think that’s a good idea.”

“Why? Is it dangerous? That sounds like fun. I’m up for a little Christmas intrigue.”

“No, not really. It’s just, look, I’m not proud of this. I’m not proud of what I’ve done. What I’m about to do. I’d rather you knew nothing about it.”

“Ha, if you’re worried it’s going to ruin your sparkling reputation, you needn’t. You’re not exactly making yourself out as the life of the party so far.”

“It’s not that. I’d just rather no one in your family was involved. You don’t need to be. You don’t need to know any more. It’ll all be sorted by lunchtime and my attention will be back on you.”

She insisted, and somehow, I convinced myself I could take her along for a drive and maybe she’d keep her word to slip down in the car seat and keep her eyes shut at the crucial moment. I’d arranged to meet Paddy, my mechanic, on the bridge by the weir at five to midday. He could help me shift the barrel into the car, and maybe act as muscle if there was any trouble. Marianne wouldn’t be much use if the shark kicked up a fuss. But I suppose she might make a useful witness to any violence that befell us. I’d just rather the stolen goods I was going to be fencing under her nose didn’t also form part of her inheritance.

In the end, however, it was the drive back from the rendezvous that was the most awkward. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the passenger’s proclaimed disinterest was lost when two young men hefted a great weight into the back of her father’s car just minutes from her father’s distillery. It hadn’t taken much for her to deduce the origin of the swag, but strangely she wasn’t angry or annoyed and seemed to find the whole thing hilarious. Apparently, it was commonplace. “Oh darling, they’re all at it!” The warehouses leaked like a cracked barrel, and all of the staff were on the make.

There was only one person who found the whole escapade funnier than Marie. Sadly for me, that was the intended recipient. We arrived in the town square a few minutes after twelve, and instead of the thug we’d anticipated meeting, we saw Allie waiting under the clock tower, apron still around her neck. Apparently, at a certain level of indebtedness, the madrina insists on ensuring payment herself. She took one look at her husband’s car, her daughter, her houseguest and her familial spirit, and laughed so hard she could barely speak. Then turned, got in her car and returned to the manse to take the turkey out of the oven.